An overview of Secure Multi-Party Computation use cases in cryptocurrency.

Multi-Party Computation describes the techniques that a number of parties with private inputs wish to compute a joint function of their inputs, without revealing anything but the output. A simple example is A and B would like to find who has more money in the bank account without needing to tell each other their bank account balance. Here we would like to learn the output of max(balance_a, balance_b) and balance_a and balance_b are the private inputs.

In this essay we first present two building blocks:

-

Oblivious Transfer (OT) - This is the most simple construction where one party’s private input is one of two values

(a, b), and the other party’s private input is a choices = (0, 1)that selects either one of the values. -

Garbled Circuit - This generalizes OT into a circuit of gates and wires where each gate is considered as an oblivious transfer with two inputs.

Then we use these two concepts in to describe Yao’s Protocol, the first two-party computation protocol. From there we can extend it to the multi-party computation called the GMW protocol. We focus on the practical steps and intuitions and briefly discuss the security guarantees, rather than covering the security and formal proofs of the protocols.

Eventually, we discuss one MPC application that is widely used in cryptocurrency custody. Cryptocurrency transaction signatures are computed jointly while each party only holds its own private key share without learning the other parties. In addition to the signature computation, several practical setups are discussed as well - key derivation and key refreshes.

Building Block 1: Oblivious Transfer

A has two values m_0, m_1 and B has a secret choice s that can be 0 or 1. Our goal here is to have A transfer the message where privacy is guaranteed:

- A does not learn about B’s secret

s. - B does not learn about

m_(1-s)from A (i.e. the message B does not choose).

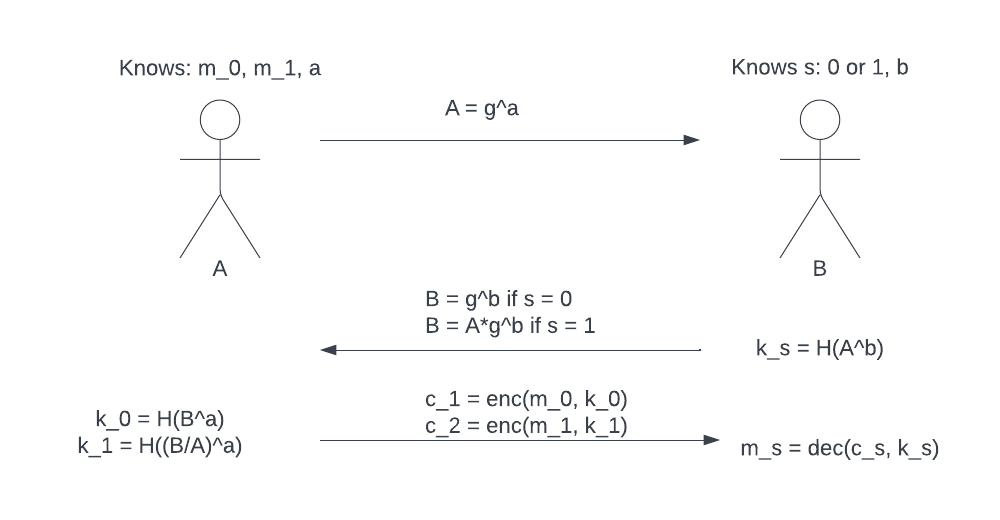

We describe the communications steps following the diagram above:

- A knows

m_0,m_1,a(A’s generated secret value). B knowss,b(B’s secret value). - B first does two things: (1) Computes his own key

k_s. (2) Sends A a valueBbased on his choices. $B = g^b$ if s = 0, $B = A*g^b$ if s = 1. Note thatBdoes not reveal anything ofs. - Upon receiving value

B, A does two things: (1) Computes two different keysk_1andk_2. (2) Encryptsm_0andm_1withk_0andk_1respectively and send both ciphertexts to B (c_1andc_2). - B can only decrypt the ciphertext chosen by

cthat reveals the message of choice:m_s = dec(c_s, k_s).

By the end, we achieve the goals that A does not learn about s and B does not learn about the m that he does not choose. The cost of OT requires 3 rounds of communication and 2 rounds of executions. Let’s trace the correctness of the two possible choice of s by plugging in the respective $k_0, k_1$ vs B value set:

- B chooses s = 0:

$$m_0 = dec(c_0, k_s) = dec(enc(m_0, k_0), k_s) = dec(g^m_0 * B^a, k_s) = dec(g^m_0 * (g^b)^a, k_s) = dec(g^{m_0ab}, A/b) = dec(g^{m_0ab}, g^{a*b}) = m_0$$

- B chooses s = 1:

$$m_1 = dec(c_1, k_s) = dec(enc(m_1, k_1), k_s) = dec(g^m_1 * (B/A)^a, k_s) = dec(g^m_1 * (Ag^b/A)^a, k_s) = dec(g^{m_1ab}, A/b) = dec(g^{m_1ab}, g^{ab}) = m_1$$

Building Block 2: Garbled Circuit

A has the input to the given function, B learns the output of the function only but not the input. In other words, the function takes in an encrypted value of the input and can output the result.

The basic idea here is to encrypt a circuit represented by wires and gates. To do this we assign a pair of keys (k_0, k_1) for every wire, such that for every gate, it is possible to compute the key for the output of the gate.

For example, A and B with a private input a, b try to find out the result of AND(a,b) without learning the private input of each other. (Note that there is some probability for you to “guess” the other person’s input if you pick a = 1 and output = 1, or if a = 1 and output = 0). Let’s define the AND gate with 2 input wires (u, v) and 1 output wire (w). Each input wire are assigned with a pair of key (k_u0, k_u1) and (k_v0, k_v1) and we wish to compute the pair of key for wire w (k_w0, k_w1). We map it to the possible value of an AND gate to a key table - we called it the garbled values:

| k_u0 | k_v0 | k_w0 |

| k_u0 | k_v1 | k_w0 |

| k_u1 | k_v0 | k_w0 |

| k_u1 | k_v1 | k_w1 |

We then encrypt the keys of the gate in the following format. To take the first row as an example, we have the encrypted value of the output of the gate k_w0 , encrypted with two of the input keys k_u0 and k_v0. This guarantees that given k_u0 and k_v0, only k_w0 can be decrypted. In other words, the receiver of this table can decrypt the value of the output, without learning anything about which input values were used to compute it. This lookup table below is called a garbled gate.

| k_u0 | k_v0 | enc(k_u0, enc(k_v0, k_w0)) |

| k_u0 | k_v1 | enc(k_u0, enc(k_v1, k_w0)) |

| k_u1 | k_v0 | enc(k_u1, enc(k_v0, k_w0)) |

| k_u1 | k_v1 | enc(k_u1, enc(k_v1, k_w1)) |

Now that we have garbled one gate, we can extend this garbled gate to many composed gates such that the output of one gate is used as an input for the next. Eventually, the final output garbled value can be decrypted to a plain value using a translation table. For example, k_w0 -> 0, k_w1 -> 0. Note that this should only be done at the final output value, not for any of the internal gates!

2PC: Yao’s Protocol

Previously we described a toy example that each party has only 1 input and there is 1 gate. What happens if A and B have multiple inputs? And the gates are composed into multiple gates representing more complex functions? Yao’s protocol applies to a representation of a boolean circuit with multiple gates and multiple inputs.

The protocol is defined as follows:

- A and B each have n input values:

a_1...a_nandb_1...b_n. - A sends B the garbled gates for all gates in the circuit (the garbled circuit), along with all the keys corresponding to

a_1...a_n. Here we define A’s input wires: $w_{a1}…w_{an}$, B’s input wires: $w_{b1}… w_{bn}$. - Now that we have all keys for all A’s inputs, how about the keys for all B’s inputs? Here we perform

noblivious transfers in parallel forb_1...b_n. For each wire i, recall that A hask_i0,k_i1and B has a choice bit s. At the end of OT, B learnsk_isand nothing else.

On efficiency, we have n OT that each has 3 rounds of communication. Each gate has a table of 4 rows where each row requires 2 encryptions. With some optimization, each output requires 2 decryptions.

MPC: The GMW Protocol

This generalizes Yao protocol from 2 to n (>= 2) parties with O(1) communication regardless of the size of the boolean circuit.

Similar to Yao’s protocol, the construction of gates still assigns two keys (garbled values) to each gate. Instead of just a random value, the randomness is a concatenation of the secret shared random values amongst all parties. This differs from the Yao’s protocol in that instead of one party chooses the keys, here we have all parties contributing to the keys.

For each gate, the party computes a 4x1 part of the table in parallel. Given the keys to each input wire, the key for the output wire is revealed. Instead of having one party to evaluate the gates in Yao’s, all parties securely compute the evaluation together in GMW.

MPC Deployment Model for Custody Setup

Now that we have the basic form of a MPC protocol, we discuss one useful MPC application where multiple parties wish to compute a valid signature for a given signature scheme. Each party has one of the keyshares and would not learn any others’ keyshares at the end of computation.

Compute keyshares

The first step is to assign a key share to each party using DKG (distributed key generation). The goal here is to construct the private inputs for each signing party. The protocol is defined as follows:

- A generates sk_a and B generates sk_b.

- A sends B an encrypted secret key

c = enc(sk_a, n)using the Paillier encryption public keyn. A also sends B a proof that thatpk_ais generated fromsk_ausing the homomorphic property.- A refresher on Paillier Encryption: Generate private key (p, q) and its public key n = pq. Encryption algorithm work as $enc(m; r) = (1+n)^x * r^n mod n^2$ where r is chosen s.t. gcd(r, n) = 1.

- This step is useful to make sure the secret key is committed and well-formed.

- They learn about each other’s public keys pk_a, pk_b and pk = pk_a + pk_b.

Securing Computing a Joint Signature

Now that each party has a secret share, we would like to compute the signature corresponding to a full private key (that either party should not have). The most well known signature schemes we cover here are ECDSA and EdDSA. You may wonder, how does one model a signature scheme in boolean circuits? The random OT model in this paper discusses the encoding of group elements and its field arithmetics in bit strings, which makes it possible to translate a signing scheme into a (large) circuit.

ECDSA:

- A has

sk_aand B hassk_b. Both learns about(R_x, R_y) = sk_a * sk_b * G - B generates an encryption of the value

k_b^(-1) * ( m' + R_x ⋅ sk_a)

EdDSA:

- A has

r_aand B hashr_b, both learns aboutR = r_1 * G + r_2 * G. - Each computes: e = H(R, Q, m)

- B sends

s_2 = r_2 + sk_2 * e mod qto A. - A sends

s_1 = r_1 + sk_1 * e mod qands = s_1 + s_2to B.

Note: r is chosen randomly instead of a function of the secret key and the message. Although still a valid signature, this makes the MPC produced EdDSA signature deviates from the RFC.

Extension: While here we describe the 2PC version of signing, there are many frameworks and optimizations to accommodate threshold setup with reduced communication cost. This paper describes a widely productionized implementation that involves a preprocessing phase with 3 rounds of communications before the signature is known, and an non-interactive phase to produce a signature share.

Key derivation

Key derivation is an important cryptocurrency primitives that allows one master private key to derive a chain of private keys in a hierarchical way. This is useful to generate multiple deposit addresses (from the corresponding child public keys) while only needing to manage one or few private keys for a custodian. The goal here is to guarantee no single party has the master private key, but we can derive the public key and have each party hold random key shares of the child private keys.

Key Refresh

Another practical aspect of MPC custody is its ability to proactively refresh key shares. This is useful to protect against the scenario that some key shares can be compromised over time.

- Generate a randomness $r$.

- Update each private key share by adding or subtracting the same randomness such that the whole key share remains unchanged. $sk_a’ = sk_a - r \mod q$ and $sk_b’ = sk_b + r \mod q$.

Some further extensions are discussed to adapt MPC for a large number of signing parties. White City constructed a set of permissioned facilitator using a trusted setup, allowing a set of permissionless parties of signers. This assumes a semi-authenticated broadcast channel.

References

-

Oblivious Transfer and Garbled Circuits: https://crypto.stanford.edu/cs355/18sp/lec6.pdf

-

Tutorials on Yao’s and BMR: https://cyber.biu.ac.il/event/the-5th-biu-winter-school/

-

Two party ECDSA: https://eprint.iacr.org/2017/552.pdf