Creating threshold signature and multisigs with Schnorr, how are they different and when to use which?

Threshold signature and multisig are two important cryptographic constructions that are available for the majority of cryptocurrency protocols. In a single signature model, it assumes that a single signer can produce a signature and submit to the protocol for verification. This makes the single private key the single point of failure, since the compromise of this key means 100% loss of funds.

Multisig and threshold signature is motivated by the demand for reliable storage of private keys. It requires that a valid signature can only be created by a threshold number of signers. If the number of valid signature shares is larger than the threshold, a valid signature can be verified.

For a t-of-n multisig or threshold signature, t denotes the minimum number of signers required to construct a valid aggregated signature, and n denotes the total number of eligible signers that could participate.

Some example applications include a wallet that is controlled by multiple stakeholders of an organization, or multiple keys in distributed geographic locations. This setup allows for tolerance of some number of compromised keys. Even when some keys are compromised, no valid signature can be produced to sign any transactions to move any funds from the wallet.

Desirable Properties

Here we describe some of the desirable properties a multisig or threshold signature protocol would like to achieve. Different protocols have different emphasis and tradeoffs among them.

- Efficiency: The round of communications required should be minimized.

- Robustness: The signing process can tolerate up to a certain number of malicious parties. Their presence would not stall the valid signature to be produced in a reasonable timeframe.

- Asynchrony: Setting timeouts are not required such that the protocol can make progress without waiting for disruptive signers. Ideally, we only assume messages between honest parties arrive eventually.

- Anonymity: The final signature should reveal nothing about the participating signers, including parameters like

tandn. - Accountability: A valid signature identifies a set of parties that participated in signing. This is the counterpart to anonymity.

- Updatability: Both

tandncan be updated after key shares are generated, without changing the aggregated public key.

Interfaces: Threshold Signature vs. Multisig

Here we discuss the API interfaces for threshold and multisig, including key generation, partial sign, partial verify, combine partial signatures and verify the combined signature.

| Threshold Signature Interface | Multisig Interface | Comments |

|---|---|---|

keygen(t, n) -> ((sk_i, pk_i) for all i, pk) |

keygen_i -> (sk_i, pk_i) |

For threshold signature, there is one aggregated public key and one aggregated private key generated. Each private key received by the participating party is in fact a secret key share. The threshold t and total number of participants n are both required to be specified during key generation. For multisig, the key generation happens independently for each participant. They each get a private key separately that does not correspond to any form of aggregated private key. |

sign_partial(m, sk_i) -> sig_i |

Same | Each participating party creates its own signature share with their private key $sk_i$. This is the same for both mechanisms. We will see later that this step usually requires more than one round of communication. |

verify_partial(sig_i, m, pk_i) -> true/false |

Same | Verifying each signature share is the same for both setup. It’s also no different from the single signature verification. The signature is verified against its corresponding public key and signed message. |

aggregate(sig_i for all i) -> sig_aggr |

aggregate(m, (sig_i, pk_i) for all i) -> sig_aggr |

This step combines the partial signatures into one aggregated signature. The threshold signature setup only requires all partial signatures. However, for multisig, all public keys corresponding to all participating signatures are also required to produce the aggregated signature. |

verify(sig_aggr, m, pk) -> true/false |

verify(sig_aggr, m, pk_i for all i) -> true/false |

In the threshold setting, the verify method only requires the aggregated public key. For multisig, the verify method function needs to know all the participating public keys. |

(Note: Aggregated signature signed over different messages is out of scope of this writing, multisig and threshold signature described here refers to signature committing to the same transaction.)

Differences and Tradeoffs

The foremost difference between multisig and threshold signature is whether the key generation step is required to be coordinated. The different nature of how the private keys are generated calls for different verification methods. Let’s break it down:

Key Generation

In the multisig setup, each signer can generate his own private and public keypair without knowing his participation in the multisig ahead of time. Therefore, this key generation is nothing special here since it does not assume a predefined threshold or a coordinated setup.

However, the key generation setup requires more care because each threshold signature participant receives (instead of generating with their own randomness) a private key share. The aggregated public key can be learned afterwards and the parameters t and n are both taken into account during generation. This gives raise to two different mechanisms:

- Centralized dealer: The most naive implementation here is that a trusted dealer can generate a global private key. By splitting the global private key using a simple yet powerful primitive: Shamir Secret Sharing Scheme, the dealer sends each party its corresponding key share.

This comes with few obvious tradeoffs: 1) The dealer is assumed to be honest that each key share is valid 2) The delivery of key share in the broadcast channel is assumed to be secure 3) The dealer is assumed to destroy the global private key.

The first one can be alleviated by having each signer provide a zero-knowledge proof for correctness. The second tradeoff can be avoided with a setup like DKG below where it is guaranteed that no one learns about the global private key.

- Distributed key generation: Generally speaking, this step runs in two rounds of communication. First, each participant acts like a central dealer of Feldman’s VSS protocol. After each participant selects a secret $x_i$, they first broadcast a commitment to $x_i$ others, and then broadcast a secret share of $x_i$.

Note: There are many variants of the DKG protocol to discuss that are out of scope of this writing, so here we only briefly mention the simplified setup. See more on this topic here and here.

Verifying Aggregated Signature

The verifier of multisig needs to know all the participating public keys for the multisig. As a result, the combined signature is not constant size: The signature length and verification time grows linearly with the number of users in the subgroup.

On the other hand, the threshold signature itself should not be distinguishable from a regular signature and so does the aggregated public key. Moreover, you notice that the threshold signature verify method is no different from that of a single signature. In other words, the verifier is unaware of the threshold nature of the signature - it can just be drop-in replacement.

This means that for a cryptocurrency protocol, a soft fork is not required to modify the verify method to support threshold signature.

In Relation to Various Signature Schemes

Musig: n-of-n Multisig in Schnorr

Here we discuss MuSig for n-of-n multisig. This is called a “partner wallet” since no key is allowed to be compromised to sign the transaction. Making t=n simplifies the security model, but it offers less flexibility to accommodate a smaller t. We will later compare this with the threshold setting FROST.

-

Broadcast partial public keys to all parties

Each signer generates keypair $(sk_i, pk_i)$ independently, and broadcasts its $pk_i$ to all parties.

Since all partial public keys are known, every party can compute the global public key. The multisig address can be derived from the global public key. The global public key is defined as the addition of each $pk_i$ with an coefficient that is relative to all participating public keys:

$pk_{aggr} = \sum_1^{n} \mu_i \cdot pk_i$ where $\mu_i = H({pk_1…pk_n}, pk_i)$

Why not a plain aggregation of all public keys like $pk_{aggr} = \sum_1^{n} pk_i$? This is to prevent rogue key attack where one adversary can broadcast its public key as the inverse of the rest of other public keys:

$pk_{rogue} = sk_{rogue} * G * \prod_{i=1}^{t-1}pk_i$

This allows the adversary to produce a signature for $pk_1…pk_{t-1}$ himself.

To prevent this, we instead multiply each $pk_i$ with a coefficient which commits to all public keys, the key cancellation scenario is not possible since the addition is de-linearized w.r.t each public key.

Alternatively, this attack can be mitigated with Knowledge of Secret Key (KOSK). The signer needs to broadcast a signature using the private key with the submitted public key. The public key is only accepted by other parties if the signature (i.e. proof of ownership of the public key) verifies. This is to make sure the public key is not maliciously constructed. However, per specified in BIP-340, the former construction is used.

-

Broadcast public nonces to all parties

Each signer calculate their partial public nonce $R_i = r_i*G$ and send to all parties.

The signature requires the correctness of $R$ to be indeed computed with $r$ that each party uses later, each signer is also to publish a commitment to the nonce. The protocol aborts if any of the commitment is not verified.

-

Each party computes a partial signature:

$s_i = r_i + c * \mu_i * sk_i$ where $c = H(pk_{aggr} | R_{aggr} | m)$

Here we see that $pk_{aggr}$ is taken into account for computing $c$. This is to prevent related-key attack where a third party can convert a signature

(R, s)for public key P into a signature(R, s + a * hash(R || m))for public keyP + a * Gand the same message m.The above 1) broadcast public keys 2) commitment to public nonces 3) broadcast public nonces consists of 3 rounds of communications.

-

Combine to get the aggregated signature:

$s_{aggr} = s_1 + s_2 + … + s_t$

-

The verify step is the same as the vanilla signature, the ${pk_aggr} and $s_{aggr}$ is submitted.

References:

-

BIP-340: The native Schnorr Signatures spec for secp256k1 for Bitcoin.

-

MuSig: The construction discussed above.

-

MuSig2: An improvement made to MuSig that reduces the communication round from 3 to 2 by having each signer to broadcast a list of public nonces instead of 1.

-

MuSig-DN: Instead of requiring each party to generate nonce randomly, this scheme defines the nonce as a pseudorandom function of the message and all signers’ public keys. When each party broadcasts its public nonce, they also broadcast a zero-knowledge proof (e.g. Bulletproofs). The tradeoff here is that the computation for Bulletproofs is relatively expensive.

FROST: t-of-n Threshold Signature in Schnorr

FROST is an extension from MuSig where the signature is fully thresholded to use $t \le n$. Compared to MuSig, it is more flexible for any t, at a cost for more communication rounds.

-

The key generation utilizes DKG consisting of two subroutines. See previous section for an overview.

-

The signing phase can be completed in $\le$ 3 rounds given different security assumptions.

2a: Preprocessing round: Each party generates

tnonce pairs and publishes their public nonces.Generated: $(d_{i1}, e_{i1})…(d_{in}, e_{in})$

Published: $(D_{i1}, E_{i1})…(D_{in}, E_{in})$

2b: An aggregator chooses some

tsigners. Then it broadcasts their nonce pairs to all other signers.2c: Each signer can then produce their partial signature:

$s_i = d_{ij} + \rho_{i} e_{ij} + H(X, R, m) * sk_i * \lambda_i$

Note that $\rho_i$ commits to the list of

tparticipating signers and the list of all signers’ public nonces $(D_{ij}, E_{ij})$. -

Now we combine all $s_i$ into the final signature (R, s) where:

$s = s_1 + s_2 + … + s_t$

$R = \sum_1^{t} D_{ij} + \rho_i * E_{ij}$

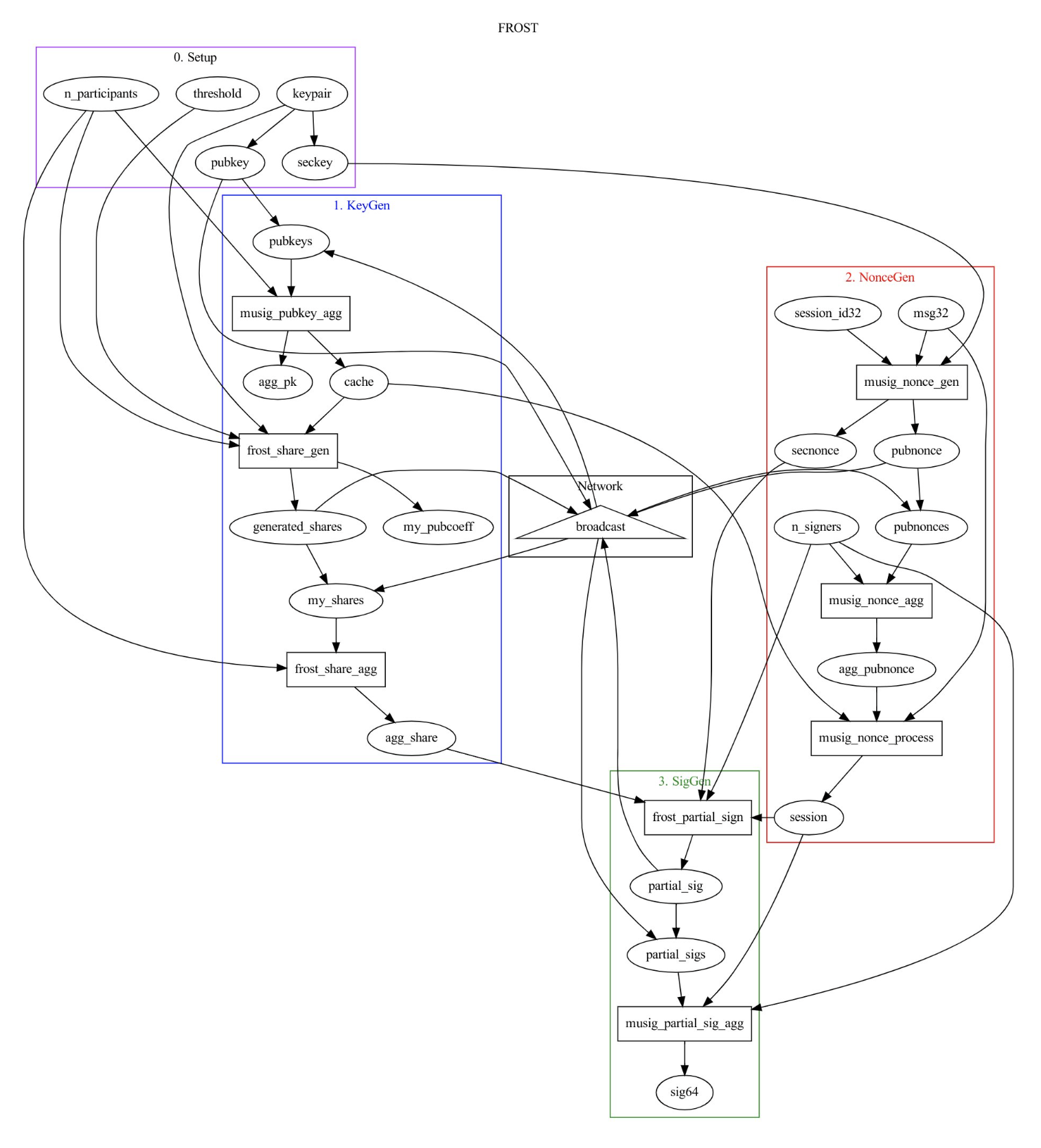

Here is a visualization of the FROST algorithm from source. We can see that the key generation (2 rounds) and the signing step (up to 3 rounds) is significantly more complicated and more expensive than MuSig2.

EdDSA

EdDSA is a variant of Schnorr signature that is defined over the Curve25519 group in its twisted Edwards form instead of elliptic curve. The Schnor multisig and threshold signature described above also works for EdDSA. However, since Curve25519 considers a cofactor that is not 1, the private key shares generated for Ed25519 requires some special processing that is out of scope of this writing. See more in detail here.

In Relation to Cryptocurrency Networks

A natural question to ask here is when to use threshold signatures and when to use multisig? Since the verify method has to be modified to support multisig, the first thing to check is whether native multisig is supported. Take bitcoin as an example, the script opcode is indeed available to use.

The benefit of multisig is that there is no need for a dedicated key generation step. In other words, the participating party can be ad-hoc and not required to be initialized in the key generation phase.

In cases where a key generation ceremony is possible with known threshold and participating parties, a threshold signature can be more flexible to adapt multiple blockchain networks. Wallets that support many networks may find the generic nature of threshold signature more desirable. In addition, since the threshold signature is no different from a regular signature, it provides better privacy for participating signers.

However, sometimes the organization may demand for more complex threshold signature setup. For example, each signer carries different weight and only a threshold of sum of weight can produce a valid signature. Or, if the amount is larger than a certain amount, 5-of-5 signature can produce a valid signature, otherwise, 2-of-5 is sufficient.

These scenarios require more expressive authorization policies and are out of the scope of a pure cryptographic solution. Account abstraction describes such use cases where the transaction execution engine can use user defined smart contracts to parse what considers a valid signature.