A closer look on key derivations with relation to curve operations.

This post is a more general discussion on key derivation applying to broader cryptocurrency usage. You can find my writing on the Sui Network specifically here.

BIP-32 and SLIP-0010 are both excellent standards on how key management works, and they both have extensive implementations across many languages. However, I struggle to find a good reading on why some constructions are needed and how they relate to the RFCs on different curves. This post examines key derivations in the contexts of signature schemes.

BIP-32 Revisited

BIP-32 defines the Hierarchical Deterministic Wallet structure to logically associate a set of keys together. This is primarily motivated by the inconvenience to keep track of a large number of private keys. The standard specifies a tree structure organizing a bunch of private keys, so they can be deterministically generated from one single master private key with domain separations. Instead of securing multiple private keys, the user just needs to secure one master key to spend the transactions.

A common use case is for a custodian that needs to associate distinct managed addresses for all of the users. By deriving a number addresses from the same master private key, each user can receive funds to his own address. Since the custodian has the master private key that can derive all the private keys, the custodian always has the ability to spend the transaction that is deposited in any of its derived addresses.

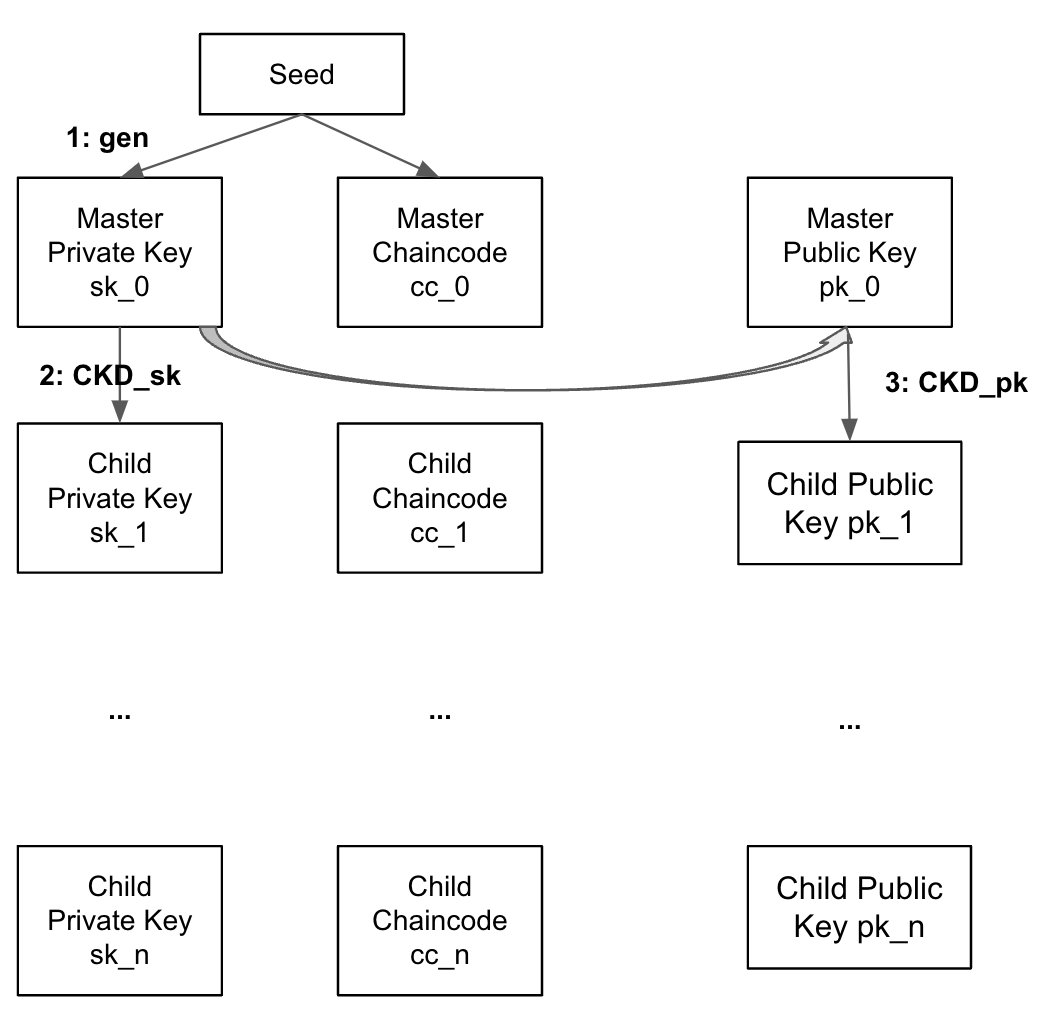

Specifically, BIP-32 defines the following three functions:

- Master seed $\rightarrow$ Master private key: This produces the first master private key and a master chaincode. Chaincode is used as additional entropy so both the public and private key derivation does not only depend on the key itself. The master public key can be calculated by multiplying the base point.

- Parent private key $\rightarrow$ Child private key: This defines the induction step for the child private key derivation.

- Parent public key $\rightarrow$ Child public key: This defines the induction step for the child public key derivation.

Now let’s take a look at the inner workings of each function.

Function 1: Master Seed $\rightarrow$ Master Private Key

$gen(seed) \rightarrow (sk_0, cc_0)$

- Compute $I$ using HMAC.

I = HMAC-SHA512(Key = "Bitcoin seed", Data = seed) - Compute master private key. This is the first 32 bytes of $I$.

sk_0 = I_L - Compute master chaincode. This is the last 32 bytes of $I$.

cc_0 = I_R

Function 2: Parent Private Key $\rightarrow$ Child Private Key

$CKD_{sk}((sk_{parent}, cc_{parent}), i) \rightarrow (sk_i, cc_i)$

- Compute $I$

- If $i$ is hardened ($i \geq 2^{31}$),

I = HMAC-SHA512(Key = cc_i, Data = 0x00 || sk_i || i) - If $i$ is normal,

I = HMAC-SHA512(Key = cc_i, Data = sk_i \cdot G || i)

- If $i$ is hardened ($i \geq 2^{31}$),

- Compute the child private key. This is the result of adding two scalars: the parent private key and the first half of $I$.

$$sk_i = I_L + sk_{parent} \mod n$$

- Compute child chaincode.

$$cc_i = I_R$$

Annotations and Comments

-

Why do we need chaincode?

Chaincode is used as the

Keyfor the HMAC function. This is to make the key derivation not only depend on the key itself but with extra entropy. We call a private key along with chaincode as an extended private keyxpriv = (sk_0, cc_0). Similarly, we have an extended public key asxpub = (pk_0, cc_0). -

What are the differences between “hardened” and “normal”?

For a hardened child, $I$ is calculated with the private key ($sk_i$) whereas the normal child one is calculated with the public key (the result of $sk_i \cdot G$).

The latter is not “hardened” because you can get it with just public keys only. It is implied that you can get the extended private key ($sk_0, cc_0$) using a parent extended public key $(pk_0, cc_0)$ and any non-hardened private key ($sk_i$).

Because $I$ is possible to compute with just the public key and chaincode, you get $I_L$ for free. Using $sk_{parent} = sk_{i} - I_L$, you can compute all the way back to $sk_0$!

-

Why 0x00 padding when computing $I$?

This is an implementation detail to make the

Datato hash the same length no matter whether $i$ is hardened or not.$pk_i = sk_i \cdot G$ is a point on the elliptic curve $(x, y)$ where $x$ and $y$ are both 32 bytes. The compact serialization form of this point is 33 bytes where $y$ can be compressed to

0x02or0x03. $x$ and 1-byte indicating $y$ can uniquely identify a point because there are only two $y$ corresponding to a $x$ that lies on the curve.

Parent Public Key $\rightarrow$ Child Public Key

$CKD_{pk}((pk_{parent}, c_{parent}), i) \rightarrow (pk_i, cc_i)$

-

Compute $I$.

- If $i$ is hardened ($i \geq 2^{31}$), fail.

- If $i$ is normal,

I = HMAC-SHA512(Key = cc_parent, Data = pk_parent || i)

-

Compute child public key. This is the result of adding two elliptic curve points: the parent public key and the scalar multiplication of $I_L$.

$$pk_i = I_L \cdot G + pk_{parent}$$

-

Compute child chaincode.

$$cc_i = I_R$$

Annotations and Comments

-

Why does the derivation fail if $i$ is hardened?

This is because the $I$ for a hardened child is computed with the parent private key that is not known in the public key derivation.

-

Why is this correct for non-hardened public key derivation?

According to the key derivation for private and public key functions, we have:

$$sk_i = I_L + sk_{parent}$$

$$pk_i = I_L \cdot G + pk_{parent}$$

The (+) here is an elliptic curve addition of two points. We can then derive:

$pk_i = I_L \cdot G + pk_{parent} = I_L \cdot G + sk_{parent} \cdot G = (I_L + sk_{parent}) \cdot G = sk_i \cdot G$

Now we have $pk_i = sk_i \cdot G$ for each child private/public key pair.

-

Why is this useful?

The ability to do public key derivation enables the use case of watch-only wallets. A common set up is to have an online service that can derive normal child public keys for receiving payments and can view balances. The offline service keeps the private key and it only will be used to create transactions moving the funds out of any of the addresses since it can derive all the private keys that control the funds.

Furthermore, BIP-44 defines the meaning behind each node in the derivation path as

m / purpose' / coin_type' / account' / change / address_index. The last two nodes are not hardened so that they can be used for watch-only wallets.

Key Generation for ECDSA vs Ed25519

So far we have covered the key derivation details for Secp256k1, this also works for any other elliptic curves. The important assumption that it works is the relation $pk_i = sk_i \cdot G$ for each $i$ holds due to the homomorphic property for addition. However, this relation is not necessarily true for other signature schemes on curves such as the Edwards curve.

First, let’s quickly recap how a public key is generated from a private key for two particular cryptosystems: Secp256k1 and Ed25519. This will help us understand the impact of key derivations on them.

Secp256k1

The private key is a randomly generated scalar represented in 32 bytes. The public key is a point on the elliptic curve, using the scalar point multiplication of the private key. $pk_i = sk_i \cdot G$ where $G$ is the generator point.

By adding some value to scalar $sk_i$ and adding the point multiplication of it to the public key, this equation still holds: $pk_i + x \cdot G = (sk_i + x) \cdot G$, because the addition of the public keys on the curve remains in the same group.

Ed25519

The private key for Ed25519 is slightly different than just a randomly generated scalar. It first involves a preprocessing step to “hash then prune” a private key. We denote the private key before preprocessing as $sk_{seed}$ and after as $sk_{pruned}$.

The seed itself is a randomly generated scalar represented in 32 bytes. The private key is pruned as follows according to the latest RFC:

-

Compute the SHA512 hash of 32-byte private key. The hash is 64 bytes $sk_{expand} = SHA512(sk_seed)$. We call the first 32 bytes $sk_L$ and the last 32 bytes $sk_R$.

-

Take $sk_L$ and prune by clearing the first three bit of the first byte and the highest bit of the last byte. Then the second highest bit of the last byte is set.

sk_L[0] &= 248 sk_L[31] &= 127 sk_L[31] |= 64

After the “hash and prune” steps, we now have $sk_{pruned}$.

-

The public key is the scalar multiplication of the pruned private key where $pk = sk_{pruned} \cdot G$.

-

Eventually, the private key used to produce an Ed25519 signature (called the expanded private key) consists of the pruned first 32 bytes of private key and public key. $sk_{expand} = sk_L \parallel pk$.

Notes

-

What does the pruning (also called bit twiddling, bit clamping) actually do? And why is it needed but not for ECDSA?

We first rewrite the pruning algorithm bit manipulation in little-endian form:

sk_L[0] &= 248 // 248 == 0b11111000 (1) sk_L[31] &= 127 // 127 == 0b01111111 (2) sk_L[31] |= 64 // 64 == 0b01000000 (3)(1) is designed to clear the lowest three bits, useful to prevent small-subgroup attack. (2) and (3) are designed to clear the 256th bit and set the highest bit, useful to prevent a class of timing attack. Interestingly, these two attack vectors are not relevant for Ed25519 signing schemes, but for X25519 key exchange which relies on the same curve. For good hygiene and compatibility for possible key generation algorithm reuse, this is adopted by the RFC for key generation for any use cases.

The Secp256k1 curve is defined in a prime-order group, but Ed25519 provides a group of order $h * r$ instead, where $h$ is a small cofactor (8) and $r$ is a 252-bit prime. This means that every subgroup of Ed25519 must have one of the following orders ${1, 2, 4, 8, r}$. Clearing three bits here basically multiplies the point by 8, making the point can possibly only be in the subgroup of order $r$.

Again, this is not a relevant attack since the generator for the Ed25519 signing scheme is known and defined to be in a prime-order subgroup according to the RFC.

Setting the highest bit has something to do with a particular way of doing point multiplication in Ed25519 curve called “Montgomery Ladder”. Based on the position of the highest bit, the multiplication is performed in variable time so a timing attack is possible to reveal some bits.

-

How does this impact key derivation defined in BIP-32?

Now that we know there is a special requirement on the Ed25519 private key: it must be hash and pruned before usage. BIP-32 does not enforce such a requirement for the master private key specified in Function 1 (Recall this is the first 32 bytes of

I = HMAC-SHA512(Key = "Bitcoin seed", Data = seed)).In addition, there are also no checks on the child private key derived from Function 2 $CKD_{sk}$ in BIP-32 would maintain this requirement. This breaks the homomorphic property for addition.

A “quick” workaround is, replacing the hashed data from $sk_i$ to the plain $sk$ before hash or pruning. Instead of I = HMAC-SHA512(Key = cc_i, Data = 0x00 || sk_pruned || i), we compute $I$ as I = HMAC-SHA512(Key = cc_i, Data = 0x00 || sk_seed || i).

A Generalized form of BIP-32: SLIP-0010

This modification is specified in SLIP-0010 as a generalized version of BIP-32 that is fully compatible with the existing BIP-32, but also provides a generalized specification to make Ed25519 key derivation work.

Similar to BIP-32, SLIP-0010 also defines the same three functions, with modifications to each one of them.

Function 1: Master seed $\rightarrow$ master private key

First calculating $I$: I = HMAC-SHA512(Key = Curve, Data = seed). Curve here is a domain separator string that can be “Bitcoin seed” (same as BIP-32) or “ed25519 seed” that can logically distinguish the master private key used for different curves.

Same as BIP-32, the master private key $sk_0$ is the first 32 bytes of $I$ and the master chaincode $cc_0$ is the last 32 bytes. Here $sk$ is assumed to be before “hash and prune” to be always valid.

Function 2: Parent private key $\rightarrow$ Child private key

While BIP-32 allows for normal and hardened child private key derivation, SLIP-0010 only allows hardened $i$ here. This is because $pk_i = sk_i \cdot G$ no longer holds for a non-hardened $i$. We would have to “hash and prune” $sk_i$ first to be able to compute $pk_i = sk_{prune} \cdot G$.

- Compute $I$.

- If $i$ is hardened ($i \geq 2^{31}$):

I = HMAC-SHA512(Key = cc_i, Data = 0x00 || sk_i || i). - If $i$ is normal: Fail.

-

(Unchanged) Compute child private key and child chaincode.

$sk_i = I_L + sk_{parent} \mod n$

$cc_i = I_R$

Function 3: Parent public key $\rightarrow$ Child public key

This step is disallowed. Because the derived public key would not match with the derived private key which assumes it is not “hash and prune”-ed.

The inability to induct public keys is, we can no longer set up a watch-only wallet for child public keys from the master public key. New address generation will always need to access the master private key.

BIP32-Ed25519 proposed a way for public key derivation by using the expanded private key $sk_{expand}$. However, there are restrictions on the max level of trees that can be only $2^{20}$ instead of $2^{32}$. Theoretically, a key recovery attack can be performed when the attacker can observe transaction spent with some child private keys.

In conclusion, we had examined BIP-32 in relation to the Secp256k1 and the Ed25519 curve. SLIP-0010 is designed to avoid the problem with non-linear key space addition to disallow the public key derivation. As a result, majority of the protocols supporting Ed25519 key derivation still prefer SLIP-0010 with only hardened child private key derivation as the only secure option.

References:

- https://github.com/bitcoin/bips/blob/master/bip-0032.mediawiki

- https://github.com/satoshilabs/slips/blob/master/slip-0010.md

- https://www.jcraige.com/an-explainer-on-ed25519-clamping

- https://input-output-hk.github.io/adrestia/static/Ed25519_BIP.pdf

- http://web.archive.org/web/20210513183118/https://forum.w3f.community/t/key-recovery-attack-on-bip32-ed25519/44